Does Purchase Price Really Matter?

Griffin and I were a bit surprised to learn that according to Pitchbook, the average private equity acquisition was done at 11.5x EBITDA in 1Q19, on a rolling four-quarter basis. At first glance, our value bias kicked in and we could not resist a snap judgement that investments made at these valuations would have a hard time delivering good returns. While it is perfectly acceptable to pay double digit multiples for fast growing, highly scalable businesses that are under-earning while they invest for the future, we doubt that is what is going on here given the typical buyout model of using stable cash flows to pay down acquisition debt. But rather than stick with our gut reaction, we decided to dig in and see what the data actually suggests about the relationship between purchase prices and subsequent returns for private equity deals.

First, public markets

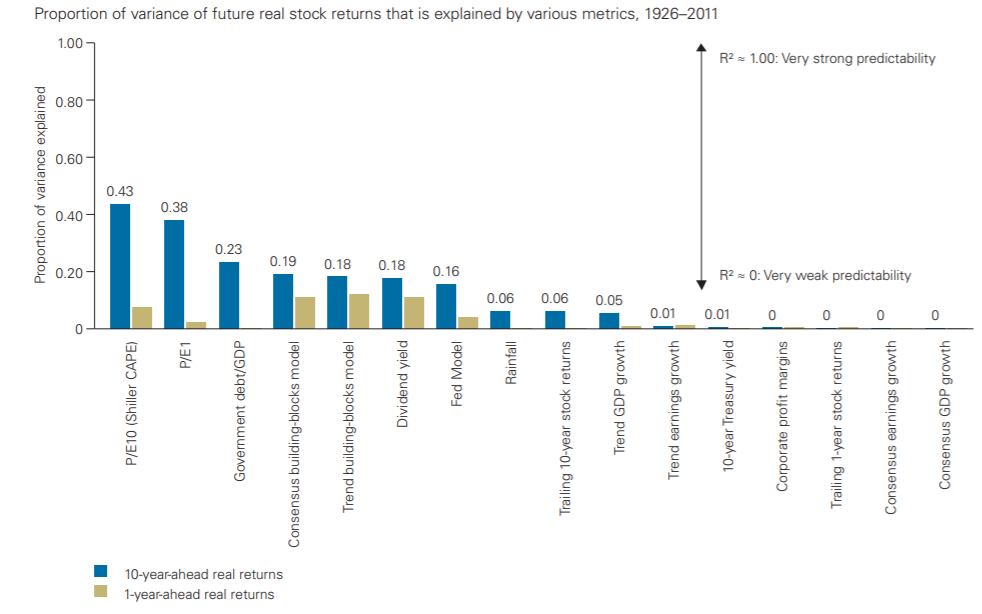

Our first step was to look at the data for public markets returns. Based on the data compiled by Yale, and subsequently reposted by Nick Maggiulli’s blog (Of Dollars and Data), there seems to be an inverse relationship between purchase valuations (in the form of price-to-earnings ratios) and subsequent returns.

Source: Yale, Of Dollars and Data

Similarly, according to a 2012 study conducted by Vanguard, “valuation measures such as P/E ratios have had an inverse or mean-reverting relationship with future stock market returns.” Their data suggest that P/E ratios have explained roughly 40% of the variation of stock returns, by far the most explanatory variable that they looked at.

Source: Vanguard

Does the same hold true for private markets?

According to Dan Rasmussen, Founder and Portfolio Manager of Verdad Capital, a systematic hedge fund focused on replicating private equity strategies in the public markets, there is a correlation of -0.69 between the purchase price paid for private equity investments in a given vintage year, and the subsequent realized return for that vintage year. While we don’t have access to Verdad’s data, it suggests that private market returns are even more reliant on purchase price than public market returns. Additionally, AQR, a quantitative hedge fund renowned for their published research, argues that purchase prices are the the most important determining factor of private equity returns.”

One public data source that we do have access to is published by CalPERS, one of the largest allocators to private equity funds in the world. Below, we show the returns (multiples of invested capital, or MOIC) of each fund that CalPers has invested in since 2000 by vintage:

Source: CalPERS, Kaho Partners

And here we plot those average vintage MOICs next to the corresponding Cyclically Adjusted PE (CAPE) yield in that given vintage year. A PE yield is just the inverse of a PE multiple, so earnings over price.

Source: CalPERS, Kaho Partners

This limited data set seems to corroborate Verdad’s findings: as yields have compressed (or valuations have gotten more expensive), average MOICs have also come down.

However, one critique to this analysis that could be made is that even if absolute private equity returns have fallen as acquisition multiples have risen, relative PE returns could still be strong (higher than the next best alternative, such as the return from investing in public equities).

A better way to measure private equity returns

An alternative to looking at private equity returns in a vacuum is called the “public market equivalent” (PME), which “compares the amount of capital generated by a private equity strategy to that generated by a public market index (the benchmark) over the lifespan of the fund, assuming similar amounts were invested with the same timing” (AQR). According to AQR, the PME “is strongly preferred by academics.” Simply, a PME of 1.1 implies 10% return above the return of the S&P 500 over the life of the private equity investment.

So what has happened to private equity PMEs? Basically, they have compressed towards earning no excess return above the S&P 500, especially when normalizing for leverage, size, and sector:

Source: AQR

Why is this? The data implies that private equity outperformance in the early 2000s was driven primarily by a valuation advantage: private equity funds were paying lower multiples for deals than were available in the public markets. See the chart below:

Source: AQR

AQR’s take seems to be pretty conclusive:

“We see that as PE has grown relatively richer and the valuation gap has narrowed, PE’s outperformance over public equities has declined, with realized outperformance for post-2006 vintages dropping to virtually zero (PME near 1), even before adjusting for size and leverage.”

Why valuations are more important for private equity than for public markets

Based on the data, it seems as though purchase valuations have a larger impact on private equity returns than they do on public equity returns. There may be a convincing reason for this.

Leveraged buyouts are by definition “leveraged,” and as a PE firm pays more for a business, the amount of debt, and thus interest costs, increase as well. So, if the EV/EBITDA multiple paid increases by 20%, the market capitalization to free cash flow multiple should increase by an even higher percentage. Dan Rasmussen writes,

“As theoretically free cash flow yields should be the driver of equity returns, if you increase the purchase price you’re not only increasing the size of the denominator in the free cash flow yield equation, because you are increasing the market capitalization, but you are also decreasing the numerator because you are adding interest cost. And so any increase in valuation actually has an almost exponentially negative effect on free cash flow yield… There’s essentially this exponential curve as you increase valuation. And so that’s what makes private equity much more price sensitive…”

Here is a visual representation of this phenomenon:

Source: Kaho Partners

While in a debt-free transaction a 10% increase in EV/EBITDA multiple leads to a corresponding 10% increase in market cap/cash flow, when a private equity buyer uses 65% debt to finance the transaction, a 10% increase in EV/EBITDA corresponds to an 18% increase in market cap/cash flow. You can see the “exponential effect” that Rasmussen refers to in the chart below plotting percentage changes in market cap/cash flow for a corresponding 10% increase in EV/EBITDA at different debt/capitalization ratios.

Source: Kaho Partners

What does all this mean for Kaho?

Increasing private equity purchase multiples are a result of more private equity capital chasing deals. Murray Stahl’s assertion that “a price earnings ratio is merely a gauge of investor interest in equities” can be applied to EV/EBITDA multiples in the private markets. Quite simply - typical private equity is very popular. Peter Mantas and Matthew Castle of Logos LP, a public equity investment partnership, offer the following advice:

“Investing is a popularity contest, and the most dangerous thing is to buy something at the peak of its popularity.”

Murray Stahl offered similar doom and gloom during the peak of the Internet Bubble of the late 1990s:

“The historical experience of investors that choose to ignore high valuation is a most unfortunate experience. High valuation is an almost certain predictor of principal loss. This loss is frequently of rather large magnitude.”

We think most private equity investors are smart, and realize that their job becomes more challenging when they pay up for acquisitions. Regardless, factors like fund structure (need to deploy capital already raised), the desire to gather assets (more management fees!), or a similar line of thinking to ex-Citi CEO Chuck Prince when he said “as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance” (FOMO), are justifying these high multiples.

Rather than ignore the writing on the wall, we think the data shows that the price paid for a business is extremely important, and that we always need to focus on valuation. Simply, if valuations are stretched for the types of businesses that traditional private equity funds are chasing, we need to look somewhere else. This means, as Buffet wrote over fifty years ago, looking for companies that “lack glamour or market sponsorship.” We think the best way to do this is finding companies off the beaten path that are not on the radar of traditional private equity funds, whether due to their size or their desire to find a longer-term partner.