To Infinity and Beyond - Part 1

Introduction

One of the most, if not the most, significant tenets of Kaho’s investing philosophy is the importance of having a long-term investment time horizon. While many pay lip service to the idea of investing for the “long term,” we have yet to see a truly comprehensive discussion of the topic. As a result, we will dedicate the next three posts to exploring the topic in depth, including why long-term investing is so rarely practiced and why it should be. Please find Part 1 below.

Investors tend to focus on the short term

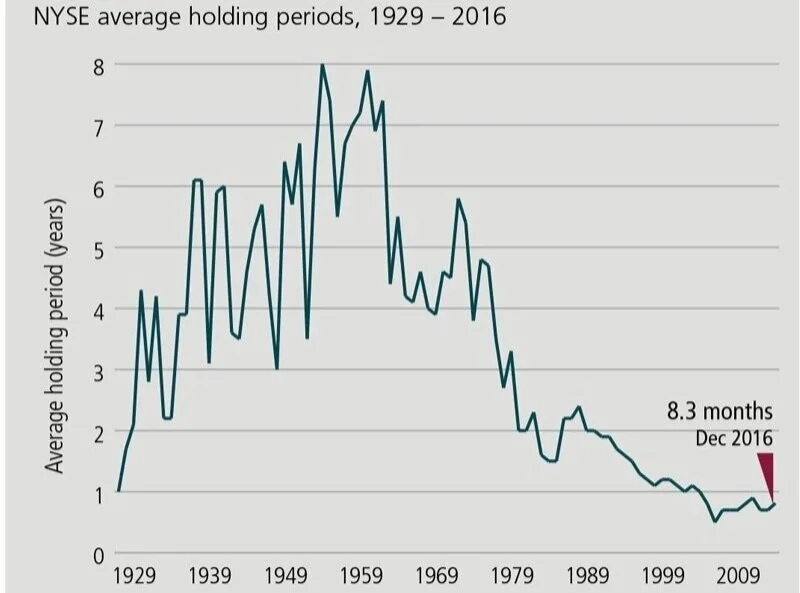

We find that a long-term time horizon is increasingly rare in the investing world. It may be obvious that public equity investors (the traders, mutual funds, and hedge funds of the world) are short-term oriented. The average holding period on the NYSE has declined to under 1 year.

Source: Ned Davis Research

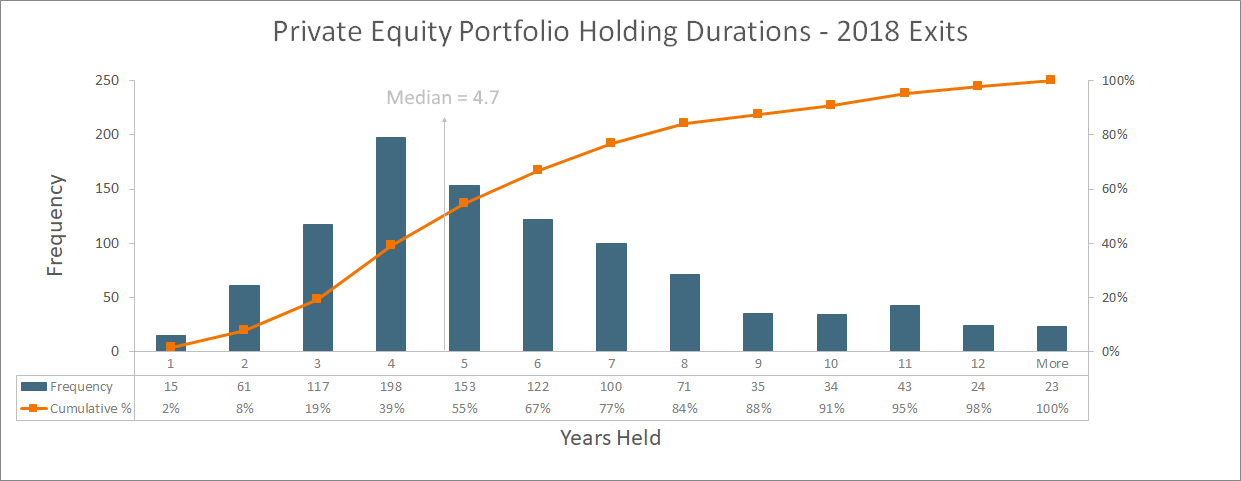

Interestingly, traditional private equity funds, while touted as a long-term strategy, are also rather short-term oriented. This may seem counter intuitive. After all, an investor in a private equity fund can expect to lock up his or her capital for a decade. But while the partnership might last ten to fifteen years, the actual investment in any one company is significantly shorter. The life cycle of a fund dictates that a firm must search for investments, deploy capital, and finally sell these companies during the ten to fifteen year window. As a result, the average holding period for traditional buyout funds is about five years, according to data compiled by Prequin and Private Equity Info.

Source: Private Equity Info.

So why are investors so short-term oriented?

Liquidity

In our opinion, investors gravitate towards short-term holding periods for three main reasons. First, they (or their clients) have liabilities that require liquidity. Whether an individual paying for college or a home, a pension fund or endowment funding an annual budget, or a company required to repay a debt maturity, all require liquidity. This liquidity often comes from selling something.

Feedback Loops

Second, human brains are actually wired to respond more favorably to short-term investment decisions. Our decision-making process is based on feedback loops. According to Thomas Goetz, author of The Decision Tree,

“Feedback loops provide people with information about their actions in real time, then give them a chance to change those actions, pushing them toward better behaviors.”

We much prefer to get this feedback immediately after deciding on a course of action because we can better appropriate cause and effect. Imagine how much easier it would be to eat healthy if we instantly dropped five pounds after choosing a salad over a burger.

If we apply this to investing, it is easy to see why an investor might prefer to invest based on next quarter’s earnings rather than the value of a business several years out. The former, a combination of volatile short-term market prices and readily available reported financial data, is an intoxicating short-term feedback loop. The latter, according to investor Nick Sleep (formerly of the very successful Nomad Investment Partnership), is less natural due to “the lag that often exists between investment decisions and eventual reward.”

Pascal

The third reason that investors tend to be short-term oriented is simply the need to be (or appear) busy. Nick Sleep sums it up well:

“[Doing nothing] is hard due to the human itch to be seen to be doing something, perhaps especially when paid a salary to be doing something.”

If we are paying someone to do something for us, we usually expect them to “work hard” to justify their rate. In investing, both general and limited partners often conflate working hard and turning over the portfolio.

This is quite similar to the idea put forward by Blaise Pascal’s famous quote:

“All of humanity's problems stem from man's inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

Up next…

Now that we have briefly touched on why investors tend to be short-term oriented, we will spend the next two posts presenting a more thorough taxonomy of why it pays to invest with a long-term time horizon.