To Infinity and Beyond - Part 3

Introduction

In Part 2, we established just how hard it is to win the short-term game: to be a successful short-term investor, you must brave fierce competition, filter through significant information noise to “buy low,” and finally manage to “sell high” in a short-enough time period to derive high annualized returns. Even if we assume that you could do this successfully, you would still be at a disadvantage versus the long-term investor. Why?

Investing for the long term eliminates reinvestment risk

An investor should be concerned with terminal value - the amount of money in your bank account at a future point in time - which requires an assumption about reinvestment rate. What good is making a high IRR investment if the time horizon was short and you cannot reinvest your gains at high rates? We think that this is a fatal flaw of traditional private equity.

Buffett illustrates the problem of reinvestment risk by using the example of a bond:

"One problem with a normal bond is that even though it pays a given interest rate — say 10% — the holder cannot be assured that a compounded 10% return will be realized. For that rate to materialize, each semi-annual coupon must be reinvested at 10% as it is received.”

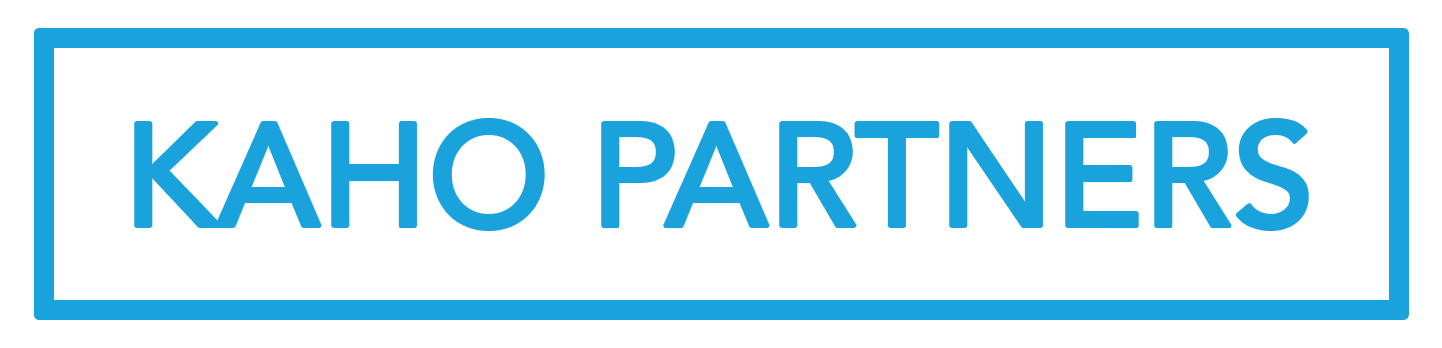

This is a somewhat convoluted concept, so consider the 10-year returns of Buffett’s aforementioned 10% bond if 100% of the coupons are reinvested at various interest rates:

Source: Kaho Partners

Clearly, the reinvestment rate matters.

If the short-term investor wishes to compound capital at high rates, he or she must constantly “rinse and repeat.” Another 50 cent dollar, another well timed exit, another 50 cent dollar, etc. This strategy requires making many more correct decisions, and thus, involves more execution risk than the long-term strategy of buying a few great businesses that can reinvest capital at high rates. The beauty of a long-term investment in a high-quality business is that the business does the work for you. You can think of a high-quality business that can redeploy its earnings back into its operations as a high coupon bond with coupons that are automatically reinvested at high rates.

Investing for the long term reduces friction costs

All of this rinsing and repeating creates friction costs. The first is taxes. Every time you sell a security for a profit, you must pay the tax man. However, if a business reinvests your capital for you (in the form of retained earnings), you don’t have to pay any capital gains tax. Let’s compare two scenarios in which you start with $10. In the first, you invest in one security, sell it for a 15% return at the end of the year, pay short-term capital gains tax (assume 30%) on that gain, and then repeat nineteen more times over twenty years. In the second, you invest in one business that generates 15% annual returns on invested capital for twenty years.

Source: Kaho Partners

In the first scenario, you will make about 4x your money over 20 years; in the second, about 7x. Clearly, the costs of taxes add-up over time. This is the power of compounding at work, and why Tom Russo writes,

“The government only gives one break to investors, and that’s the non-taxation of unrealized gains.”

Another type of friction costs are transaction costs - fees and expenses paid to intermediaries. These costs are more important in the private markets, where fees paid to accountants, lawyers, bankers, and even private equity funds can add up. According to Tom Blaisdell, Executive Director, Center for Private Equity & Entrepreneurship (CPEE) at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College, fees and expenses tend to be ~5% of the value of the target company.

We find that the peculiar example of the “sponsor-to-sponsor sale” or “secondary buyout” (one private equity fund selling to another) perfectly illustrates the drag of transaction costs. This phenomenon is interesting because there is clearly still value in the underlying business (or why would the second sponsor be buying), but the short time horizons of typical PE fund structures require the first sponsor to sell. According to Preqin, there were 746 secondary buyouts in 2018 totaling $128 billion globally, up 50% vs. 2017.

Source: Prequin

In a sponsor-to-sponsor sale, there is significant value destruction compared to if one owner continued to hold the underlying business. Assuming a sale for more than carrying value, the seller must pay capital gains tax. The buyer likely pays a takeover premium. And both sides must pay their bankers, lawyers, accountants, and consultants.

Reducing friction costs is not trivial. As successful long-term equity investor Terry Smith recently wrote in a letter to his investors,

“Minimizing the costs of investment is a vital contribution to achieving a satisfactory outcome as an investor.”

Investing for the long term protects the investor from the grave mistake of selling a great business

Being a long term investor doesn’t prevent you for selling a business, it just means that you don’t have to. But a short term investor must sell, and thus may commit perhaps the worst mistake in investing: selling a great business.

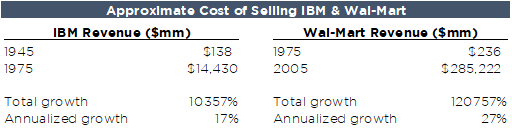

Investor Nick Sleep wrote about a large institutional fund that during the 1970s compiled a list of all of their historical mistakes. The fund discovered that selling IBM in the 1940s was the single largest mistake they had ever made. If the fund had instead held IBM to the then current date, their stake in the company would have been worth more than their total assets under management. As a result, they vowed never to make the mistake of selling a terrific business again. Interestingly, around the same time, the fund made the decision to sell their entire position in Wal-Mart. Thirty years later, their position in Wal-Mart would have again been worth more than their entire AUM…

Source: Kaho Partners

The mistake of selling a great business can be so costly because the downside is unlimited. It’s shocking how many of even the truly great long-term investors say that their worst investing mistake was selling a great business:

“The sacrifice of upside by selling the shares [of a great business], the worst sin of commission we ever made, was painfully expensive. The failure to not capture the real upside was gargantuan.” Chris Bloomstran, Semper Augustus Investments Group

“I have done a terrible job in terms of selling. I think selling is a lot harder than buying. And I think many times, we've sold too early… I would say, historically, we've been, I think, too quick to pull the trigger. I think that when you find yourself owning a fraction of a great business, it’s usually a mistake to let go.” Mohnish Pabrai, Pabrai Investments Funds

“We have argued that the biggest error an investor can make is the sale of a [great business] in the early stages of the company’s growth. Mathematically, this error is far greater than the equivalent sum invested in a firm that goes bankrupt. The industry tends to gloss over this fact, perhaps because opportunity costs go unrecorded in performance records.” Nick Sleep, Nomad Investment Partnership

“I have learned that selling a stake in a good company is almost always a mistake.” Terry Smith, Fundsmith

“If I’ve made one mistake in the course of managing investments it was selling really good companies too soon.” Lou Simpson, GEICO

“It was a mistake [to sell McDonald’s]… And I would say that this particular decision has cost us in the area of a billion dollars-plus.” Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway

“To sell off something that is a really wonderful business because the price looks a little high… is almost always a mistake. It took me a lot of time to learn that.” Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway

Conclusion

At Kaho Partners, we believe in the importance of a long-term investing time horizon, not because it sounds good, but because it pays.