Valuation, Demystified - Part 1

Introduction

The only reason a rational investor would invest a dollar in a business - whether a private company or a publicly traded stock - is because they expect to get more than a dollar back in the future. Otherwise, the investor should just spend their money on something else. Warren Buffett summed it up perfectly when he said:

"The first investment primer that I know of, and it was pretty good advice, was delivered in about 600 B.C. by Aesop. And Aesop, you'll remember, said, 'A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.'"

You see, a business is by definition worth whatever it will pay back to the investor over time. Or as academics might say, a business is worth the sum of all future cash flows it will distribute to its investors in perpetuity, discounted back to present time at an appropriate discount rate. While this definition is theoretically sound, it is practically useless. Businesses, their economics, and their financial results are much too noisy and unpredictable to model out future cash flows precisely. What the market will pay for a business - or the required discount rate - is even noisier and more unpredictable.

At the same time, heuristics like relative P/E multiples say nothing about the intrinsic value of a business. Why is 13x cheap and 20x expensive? Might you pay a higher multiple for a better business? How much higher? Is Apple at 18x worse value than General Motors at 6x?

This illustrates the two problems with the traditional valuation frameworks (discounted cash flow analysis and valuation multiples) - one is unwieldy and the other is overly simplistic; neither is particularly helpful. So what do we do?

Our Approach

Before we dig into our specific methodology, it is worth noting the five core principles we always keep in mind when thinking about valuation.

Avoid false precision. Assigning a pinpoint valuation to a business is a fool’s errand; think in possibilities and ranges.

Focus on expected rate of return. It is much better to think about expected rates of return at different prices than to assign a fixed valuation to a business.

Use first principles. Start with economic and mathematical realities and work from there.

Keep it simple, stupid. Avoid the temptation to get too cute.

Embrace opportunity cost. The most important “first principle” of valuation is that it’s based on a comparison with your next best alternative.

Our framework is pretty simple: we try to figure out roughly what our expected return will be from investing in a particular business at a particular price and then we compare it to our opportunity cost.

Expected Return

We use the following formula for expected return because it’s simple, easy to understand, and based in economic reality.

Expected Returns = Dividend Yield + Growth + Change in Valuation

Basically, an investor’s expected return is based on the cash flow received compared to price, the growth of that cash flow, and what another investor might be willing to pay for the same asset in the future.

This might seem out of left field, but in reality it is just a reworking of the classic ‘Gordon Growth’ or ‘Dividend Discount’ model below, with the added term ‘Change in Valuation’ tacked on at the end.

Gordon Growth Model:

Price = Dividend / (Expected Return - Growth)

Here are a few clarifications:

By ‘Dividend’, we mean normalized distributable cash flow, or the cash flow a business could pay to investors this year.

‘Growth’ refers to growth in distributable cash flow. Assuming the payout ratio remains constant, this would also equate to growth in earnings and growth in book value.

We are talking about annual returns, so by ‘Growth’ we mean annual growth in distributable cash flows, and by ‘Change in Valuation’ we mean annualized change.

Here’s a simple example:

A stock costs $100, dividends are $5, and cash flows are growing 5% per year.

Expected Return = ($5 / $100) + 5%

An investor would earn a dividend yield of 5% and 5% growth, for a total expected return of 10%.

‘Dividend Yield’ and ‘Growth’ are intrinsic to the business and price you pay, while ‘Change in Valuation’ is all about what the market is willing to pay and thus extrinsic to the business. This valuation is driven by opportunity cost, but let’s ignore change in valuation for now and assume that we hold the investment forever without selling it.

An important nuance is that dividends (distributable cash flow) and thus the dividend yield are really an output of a business’ economics, rather than an input. Dividends are determined by the percentage of earnings a business can sustainably distribute while maintaining a certain level of growth. This “payout ratio” is itself determined by the business’ underlying returns on equity (ROE). As such, the derivation of a sustainable dividend is:

Dividends = Earnings x Payout Ratio

Payout Ratio = 1 - (Growth / ROE)

Dividends = Earnings x (1 - (Growth / ROE))

Now, it is easy to see that knowing the price, earnings, ROE, and growth give you the ingredients to estimate an investment’s expected return. We can put that together with the following formula:

Expected Returns = (Earnings x (1 - (Growth / ROE ))) / Price + Growth + Change in Valuation

Here’s another example:

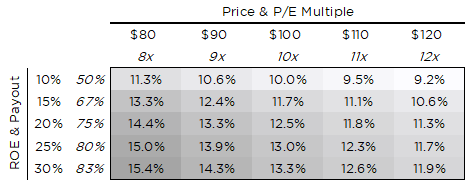

A stock costs $100, earnings are $10, dividends are growing 5%, and the business generates a 20% ROE.

Expected Return = ($10 x (1 - (5% / 20%))) / $100 + 5%

In order to grow 5%, the business must reinvest 25% of its earnings, as 5% / 20% = 25%. If 25% of earnings are reinvested, 75% of earnings, or $7.50, can be paid out to shareholders. The dividend yield is then $7.50/$100 = 7.5%. Adding the 5% growth gets you to a total expected return of 12.5%.

Below, you can see how the expected return for this particular investment ($10 of earnings growing 5% per year) changes as price and ROE vary:

Source: Kaho Partners

So we’ve outlined our valuation framework, but we still have left some questions unanswered: First, what is a “good” expected return anyway? Second, how should we think about changes in valuation? In order to answer those questions, we have to discuss opportunity cost.